| Article Overview:

How did Iraq and Iran, and the Middle East come to be as they are today?

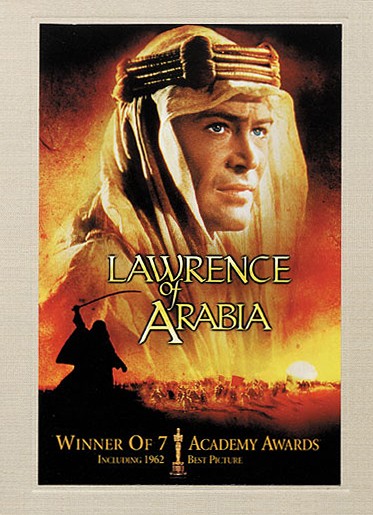

For those wondering why the Middle East is a puzzle, the movie

Lawrence of Arabia is a great historical teacher. Viewing

it is not only entertainment, but a journey toward understanding the

massive conflicts the United States faces in reconstructing the

desert. |

VigilanceVoice VigilanceVoice

www.VigilanceVoice.com

Monday--August

4, 2003—Ground Zero Plus 691

___________________________________________________________

Lawrence of Arabia--A Roadmap To

Understanding Terrorism In The Middle East

___________________________________________________________

by

Cliff McKenzie

Editor, New York City Combat Correspondent News

|

GROUND ZER0, New York, N.Y.--Aug. 4,

2003-- In the opening minutes of the classic film, "Lawrence of

Arabia," a Bedouin guide bringing T.E. Lawrence to see Arabic Prince

Feisal is shot in the head by a rival Serif played by Omar Sharif.

The Bedouin's crime was drinking water from another tribe's well.

Drinking water belonging to another without permission was punishable

by death.

|

|

Movie

synopsis: Sweeping epic about the real life adventures of T.

E. Lawrence, a British major who unified Arab tribes and led them

in the fight for independence from the Ottoman Turks in the 1920s |

The scene is momentous, for it

serves as an example why the Middle East is a nation of tribes,

divided and walled by centuries of conflict, and suggests the legacy

of conflict between tribes may take more than America's occupation of

the countries of Afghanistan and Iraq to bring even a portion of the

Middle East into a state of unity.

Bookending the opening scene is another startling example of

the difficulties America and its allies faces. It occurs near

the end of the movie when the Arabic tribes take over Damascus under

British Major Lawrence's leadership. The newly formed Arab

National Council engage in a bitter tribal fight over who is in charge

of the electricity and telephones. Unable to resolve their

personal conflicts, the tribes leave Damascus to the British who are

technically skilled in keeping the engines of urbanization well oiled.

Between the opening and ending of the 1962 Academy

Award winning film that runs 227 minutes, lies countless pools of

blood, sucked up hungrily by the thirst desert.

Death, it appears, is like swatting flies, as Lawrence

of Arabia quickly finds when he must execute the very man he saved

from the desert's cruel sun to keep the peace between tribes about to

join in the attack on the port of Accaba. Actor Anthony

Quinn, playing a rival tribal leader who is more mercenary than

loyalist, tells Lawrence, brilliantly played by Peter O'Toole:

"You gave life, now you take it."

|

|

"You gave

life, now you take it" -Auda abu Tayi |

It has been a number of years

since I've watched the movie, and never have I viewed it with more

interest than now, in the wake of the challenges the United States

faces not only in Iraq, but as it ventures into West Africa to tackle

the bloodshed and violence in Liberia.

As a westerner, born into a technologically advanced

civilization, I take for granted the things of comfort such as running

water, electricity, hospitals, police, public safety and the freedom

to travel and drink out of water fountains without fear of being shot.

The land of the desert is harsh, and the

people who live in its shifting sands are even more harsh in their

hunger to protect their legacies of beliefs.

In Iraq and Iran, there are great barriers

standing between the tribes, some that may be temporarily, or perhaps

forever, insurmountable.

|

|

Despite its

pristine beauty, the land of the desert is harsh, and its people

are even harsher in their hunger to protect their legacies of

beliefs |

Lawrence of

Arabia re-emphasized for me the complexity of the Middle East, and

caused me to better appreciate a culture and its rich history I often

think I understand.

In a tragic message that America and other

western nations engaging in the Middle East might wish to deny, even

Lawrence of Arabia was unable to assimilate the ways of life.

Peter O'Toole, in a great scene of frustration, pinches his white skin

and looks painfully at his close friend, Serif Ali ibn el Kharish,

played by Omar Sharif, and cries: "I cannot change this."

|

|

Peter O'Toole

earned an Academy Award for his role of Lawrence of Arabia

in the movie |

He bemoans he is

white, born English, not Arabic. At that moment, you know

if he could have one wish, it would have been to be born Middle

Eastern so he could become truly part of what he was fighting for, and

not stand on the outside of the ring looking in.

|

|

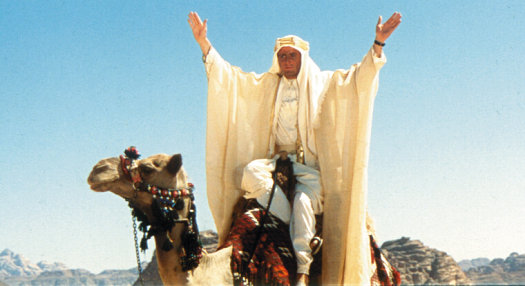

Colonel T. E.

Lawrence led the people of the Arabian peninsula to independence |

It is easy to look at the

tribal warriors as Terrorists, seeking to inflict Fear, Intimidation

and Complacency upon others for the sheer sake of Terror.

While this might be true of some, there is something deeper that comes

out of the film, at least, for me.

It was the message of brutal violence resulting

from generations of brutal life. Life and death had

little difference in the film, evidenced by the tragic loss of two

young orphaned companions of Lawrence who died in his service, one

sucked down in a hole in the sand, the other killed by Lawrence so the

Turks would not torture him after the boy was wounded by a detonator

that ripped open his belly.

Lawrence of Arabia is a look behind the veils of

the Middle East. It shows the Arabs fighting in the 1920's for

their independence from the Turkish Ottoman Empire, and reminds us

that the struggle for independence has been long and bloody.

Even though thousands of years are vested in the

history of the tribes, little time has been given the people to learn

to live as one.

I thought of the United States and its allies as

being a sort of Lawrence of Arabia in the 21st Century.

As Major Lawrence sought to unify the land and bring peace and

prosperity to the sand, so is America trying to rally the tribes to

act as one.

But then I thought about the ending of the film,

and the scene with the tribes trotting away from the heart of

civilization back to their tents and sand, to live a life void of many

things we treasure.

|

|

Lawrence

(O'Toole) was successful in getting the tribal chief Auda (Quinn

on the left) and Ali (Omar Sharif on the right) to work together |

I was reminded of the

final words of Anthony Quinn, who plays Auda abu Tayi, the mercenary

tribal chief. As Lawrence is sitting defeated in the empty

hall where he attempted to get the tribal chiefs to work together in

Damascus, Quinn urges him to come with him to the desert, to leave

behind the trappings of civilization.

"This," Quinn says waving at the buildings, "this all

means nothing."

In a way, he is correct.

We fight to civilize ourselves with conveniences, and

become so dependent on them we forget they are our servants and become

slaves to them. When the lights fail we become afraid of

the dark. When noises frighten us we cower.

When our feelings are hurt we cry "victim" and lash out in revenge.

|

|

Watching

Lawrence of Arabia might help us in our Vigilant understanding of

our roles with other nations |

In ways, the desert life

was without Terror, for it took constant Courage, Conviction and Right

Actions to survive.

Modern life, at least in the eyes of the tribes,

was Terror. To rely on a light switch or a water spigot,

or someone to protect you from harm, all ran in opposition to the

beliefs of the tribal chiefs.

Perhaps, if we all watched Lawrence

of Arabia again, and thought of our role with other nations, we might

find our quickness to change their way of lives tempered with a

reality that they might know more than we about Vigilance.

Aug

3--Burying The Bodies Of Terrorism

©2001

- 2004, VigilanceVoice.com, All rights reserved -

a ((HYYPE))

design

|

| |

|

|